Source : Deccan Herald

Source : Deccan HeraldThere are hundreds of reports every year of students dying in similarly mismanaged coaching centres in urban India. The deaths mostly have to do with awful conditions in these centres — exorbitant costs, extreme pressure, inept counselling, claustrophobic accommodation, dark libraries, underground burrows for classrooms, overcrowded, dingy hostels and substandard food.

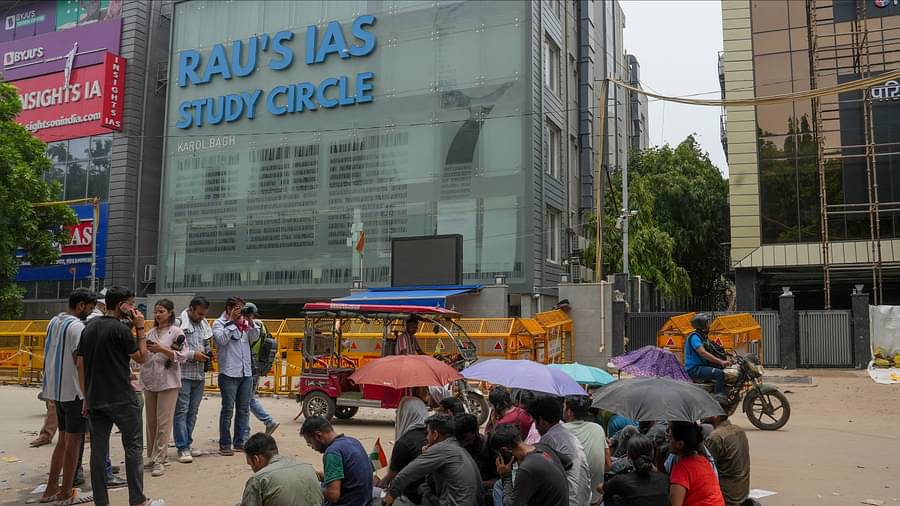

The death of three young UPSC aspirants in a dark Delhi basement is gruesome. It appears to have resulted from the IAS coaching centre’s negligence, prioritising cost-cutting rather than a safe study environment.

There are hundreds of reports every year of students dying in similarly mismanaged coaching centres in urban India. The deaths mostly have to do with awful conditions in these centres — exorbitant costs, extreme pressure, inept counselling, claustrophobic accommodation, dark libraries, underground burrows for classrooms, overcrowded, dingy hostels and substandard food. Also Read: Coaching centre deaths: Delhi court disposes of bail pleas of co-owners Many of the aspirants come from low-income families. They somehow manage the costs of trying their luck to become engineers or doctors, get a UPSC rank, or land a government or bank job. Coaching centres seem to be the only means available to help them reach their aspirations. The Delhi deaths are a wake-up call for the government — and there have been many such calls. The official reaction is formulaic: announce ex gratia, arrest the owner of the coaching centre, lock down the premises, issue fiats about safety and hygiene and maybe even set up committees to review the issue. Such episodic reactions are meaningless. The root problems remain unresolved. For instance, do the centres return the fees to the victims’ families, and is this done promptly? What about the other students who miss classes because the centres are closed? How are they repaid? These incidents involve much more than the skewed relationship between the aspirant and the coaching provider. They must be viewed in the larger context of the relevance of India’s present education system, entrance examination processes, the nature of work, employment structures, demographic equations and the ever-expanding aura of technology. Also Read: Delhi coaching centre tragedy: MCD to set up four libraries in name of UPSC aspirants who died last month As student dependence on coaching centres remains a reality for the near future, there is an urgent need for clear and cohesive policy for the regulation of the sector. The lack of a framework has continually put not just students’ futures, but also their safety and lives at risk. The need of the hour is education reform that targets institutions and coaching centres to set basic standards in place – for quality, infrastructure, fees and maintenance. Unorganised, unregulated The business of coaching students to prepare them for various entrance examinations is perhaps the most significant unorganised and unregulated sector in India, after the migrant labour sector. Millions of big and small centres crowd metros and towns, catering to the ever-growing aspirations of youth.

Remember, as much as 60% of the country’s population is under 35; adding to the immense pressure of finding jobs. Around four crore students are presently enrolled in coaching centres in India. (This apart, nearly seven crore school and college students go to tuition.) Every time a student enters a coaching centre, they add to the revenue of the coaching business, estimated at around Rs 58,000 crore. According to some reports, it may rise to Rs 1.4 lakh crore by 2028. Also Read: 'Have they lost it?' Delhi High Court on police arresting SUV driver for coaching centre deaths Note the correlation between the young demographic, crowded coaching centres and the high coaching revenue. It tells you how big the market is and how high the hunger for jobs is. No government can fulfil this demand for jobs without additional collaboration and investment. There are insufficient government jobs, and they are shrinking yearly, as the government pares down its public sector presence. Also, the increasing role of technology and the need for advanced skill sets are leading to lateral entry into mid-level government jobs, eating into the number of traditional jobs. The answer to all of this is well-known. The focus must shift to entrepreneurship, self-employment or the private sector. Yet, ask the teeming millions at coaching centres, and the aspirants will tell you that government jobs are their priority. Limited jobs The government occasionally encourages, even nudges, the private sector to increase its annual intake numbers. However, that depends on the nature of the demand-supply equation and industry expansion plans. No company or industry can guarantee employing a specific percentage of fresh employees yearly. The private sector, in turn, counters by questioning the employability of the millions graduating from universities and vocational institutes. Official platforms endorse this view. The Economic Survey 2023-24 says only 51.25 per cent of India’s graduates are employable. NASSCOM (National Association of Software and Service Companies) has also flagged a significant employability gap among engineering graduates in India. Why so? Because of a significant skills gap. According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey, the unemployment rate for youth is rising dangerously in 2024. This points to a lack of skills, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. Why are students not equipped with skills? Students aspire to be in the formal education system, and only when they cannot do so do they look out for vocational skill development institutes. However, there needs to be more skills training in the formal education sector. The quality needs to be standardised. The syllabi need to be updated regularly.

After a long gap, the top IITs revised their syllabus recently, acknowledging the reality that education must match industry needs. Only a few institutions impart experiential or hands-on training. Many youth need more effective counselling to take vocational courses after their Class 12. That is because there is no coordinated system to direct them towards self-employment by extending banking and infrastructural support. The National Education Policy 2020 proposed introducing outcome-based learning with a flexible, multi-disciplinary system. However, it suffers from too many grey areas. The students, for the large part, are dependent on a system that focuses on rote learning, thereby swallowing the space for discussion and analysis-based learning. Peer, parental and institutional pressure to perform forces students to look for avenues outside the education system to perform better in exams. As a result of the failure of the mainstream education mechanism, there is a growing dependence on private tuition and coaching classes. The government has attempted to control and regulate this alternate system, but in vain and it remains too widely spread to be regulated. However, like the gig economy, which is now being given official recognition, the alternate system can be deemed an industry and be subject to monitoring by a national regulatory authority. However, taking this route will not solve the problem of the student being forced to seek support from a private coaching centre. As we have seen, the failures are at multiple levels, stemming from the lack of a cohesive and comprehensive national programme within a school-to-employment framework. A single-window system that recognises the linkages between education, skills development, higher education counselling and employment is needed. (Venkata Vemuri is an independent journalist and commentator based in Delhi)